What It’s Actually Like to Live Andrew Huberman’s Daily Routine

Andrew Huberman, a Harvard associate professor of biology, is “extremely jacked,” as GQ put it recently. Huberman is probably more famous due to his podcast, Huberman Lab, which has over 3 million monthly Youtube subscribers. But really, the “jacked” feel of the man extends to the podcast, too: Using comprehensive and convincing epidemiological evidence, Huberman covers a huge range of topics from the benefits and risks of MDMA to emotional and social learning, tools to improve fitness, and even how smells impact our biology.

Huberman and his podcast are calm, measured, and intensely science-based. This pleasant nature, paired with his wealth of knowledge, lend the sense that this guy has figured things out.

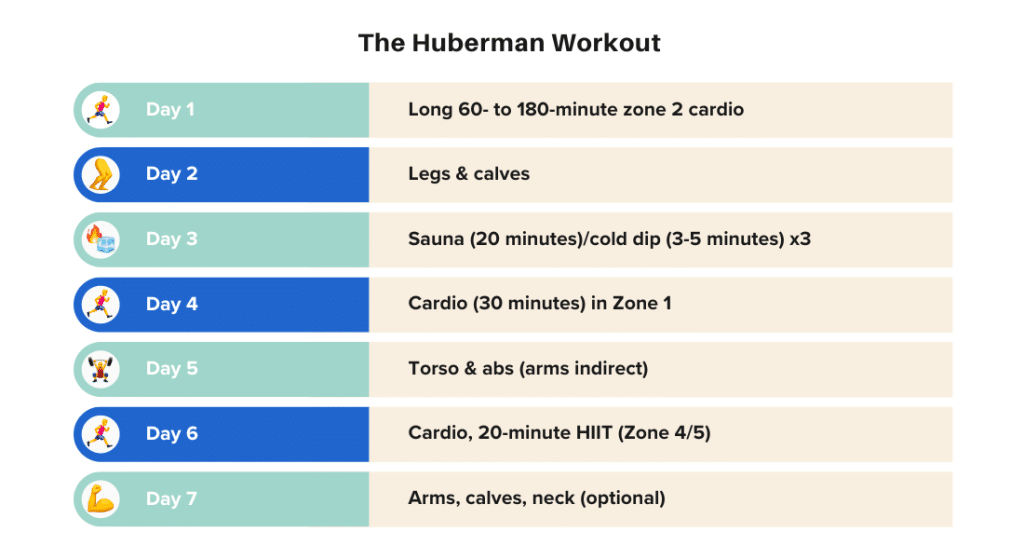

Huberman’s daily routine and habits are not for the faint of heart, though: Intermittent fasting, delayed caffeine intake, seeking natural sun first thing in the morning, eating fish oil, yoga nidra, sun soaking, and cold plunging are all part of the man’s daily routine. In the spirit of Huberman, I decided to try out his daily routine for a week to see how it affected my own life—for science.

Morning

Sunlight exposure

“The first thing I do after waking up in the morning is make a beeline for the sun,” Huberman has told the Modern Wisdom Podcast.

My dog, Fish, must be a big Huberman fan. He wakes me up “naturally” every morning around 7 a.m., insistent on a walk. And because I live in Los Angeles, sunlight is never in short supply. This week, I paid some more attention to the warmth and UV rays. Sunlight in one’s eyes, Huberman says, “sets in motion a huge number of neurobiological and hormonal cascades that are good for you, reduces stress late at night, offsets cortisol, and does a million other different things that are good for you.” In particular, Huberman calls for early sun, so-called “low solar angle sunlight,” which has more yellow-blue contrast. This provides “optimal stimulus for neurons in the eye that wake up the brain and the rest of the body,” Huberman said.

I found it surprisingly painful to corral bright sunlight into my eyes, and was sure to follow Huberman’s instructions, per that GQ interview:

“I don’t stare at the sun, but I’ll allow myself to blink. You can even look down at your phone or a book, that’s fine. But you don’t want to be with a hat or a hoodie and cloaking your eyes from the sunlight. You want to get that sunlight in your eyes. You want to do this for about five to ten minutes.”

This is, according to Huberman, great for my sleep, my energy, my mood, my wakefulness, and my metabolism, among other things. Even given the glare, this felt like an easy win, given Fish’s encouragement. Good dog.

Center yourself

Another Huberman morning habit to enjoy (and be initially confused by): wrapping one’s brain around its place in the universe.

“I will focus on some external object about a foot or two away, and I’ll try and anchor my attention to that location,” he’s explained. “And then I’ll look at some more distant location, ideally way off in the distance. And then I will also do it to the horizon if I can see the horizon, the most distant location I can see. And then I imagine myself doing this practice and I think about how I’m existing in the entire globe, which is existing in the universe, right?”

Huberman is a believer in the idea that there’s a lot of power in controlling our perception. “All I’m doing is deliberately stepping my vision, and therefore my cognition, to different places in physical space,” he says. “And in doing that, we know that we are allowing the brain to shift to different time domains.

Even better, Huberman claims this method will help with focusing attention for as long as needed on a single task—personally, my current mental health holy grail.

I found awareness of this sort of spatial and time difference massively anchoring in my day-to-day happenings. Sure, I am but an ant in the massive warren of Los Angeles, which in and of itself is a very small anthill on the planet earth, which is itself but a mote of dust in an ever-expanding universe. But rather than causing dread, I felt this sort of thinking lent my brain a simple and honest reality to chew on—and this freed me to go on doing the dishes without worrying about the littler, uglier, constant thrum of little-existence terrors like bills, thank you cards, and upcoming formal functions.

Delayed caffeine

Once, when I lived out of a van for a summer, driving around the country, I delayed my caffeine intake. This was not intentional; most mornings I just didn’t have the time nor energy to make coffee first thing when I woke up—it was straight to hiking or fishing, or else driving 14 hours to our next destination. Coffee was a refilled muga at 10 a.m. or so, at the nearest gas station.

And it was great, actually. Huberman delays his morning caffeine with some extra intention and bio-logic.

“If you have a hard time waking up in the morning, or you’re groggy mid-morning, you might try delaying your caffeine intake,” Huberman said on an instagram post. Adenosine, a compound that builds up as we sleep, doesn’t clear the brain properly when we drink caffeine—an “adenosine antagonist”—immediately after waking. Drinking caffeine later, then, can help those who have trouble waking up or feel sleepy around midmorning.

I didn’t mind pushing back caffeine by about 60 minutes every morning. I’m not so addicted that my body and brain cried out for the caffeine; and the extra time just made my first espresso even more delightful—like I’d earned it. Another bonus effect of delaying caffeine, Huberman notes, has to do with stress hormones. Slug the joe right when you wake up and you could lose a natural surge of adrenaline and cortisol, which makes you feel good just for being awake and alert. Perhaps that was why waiting a little while to fuel up made me feel so good?

Intermittent fasting

Another Huberman-schedule delay: breakfast. In fact, Huberman often skips breakfast entirely, fasting till noon before eating a low-carb meal. He does have a glass of AG1 greens powder every day, though that has more to do with its massive vitamin and mineral load than it does calories.

Usually, I dabble in breakfast, but again this Hubermanism worked surprisingly well for me. When I wake up with lots of water and delayed caffeine (see above), I can feel my body working throughout the morning; I feel sharp, lean and mean. By the time I’m needing a break around 1 p.m., I’m hungry but not starving.

Intermittent fasting has been linked to weight loss, which I’ll take. More importantly, he notes, IF seems to have a “powerful and positive” impact on various health parameters linked to a better healthspan, including decreased blood pressure, lowering oxidative stress, and decreased inflammation. This is part of the reason so many other longevity experts subscribe to it in some fashion. The good news: It’s relatively easy to get started.

Afternoon

Cold plunge, hot shower

“After the sauna / jump into some freezing cold water,” as Action Bronson puts it. Or, in Huberman’s case:

“I’ve taken to getting into the cold plunge (or a cold shower) for one to three minutes before a workout, usually after getting sunlight some time early in the morning. And by the way, I definitely take a hot shower at the end.”

According to Huberman, this causes “a big surge in cortisol, a big surge in adrenaline, epinephrine, dopamine.” Though some dopamine hits can be huge with a huge “crash” afterward (bad), a cold shower causes “big surges in dopamine that are long-lasting… and are huge elevators for mood and alertness and wellbeing.”

An embarrassing truth: I often work from the bathtub. Seeking this dopamine and adrenaline surge, I decided to intersperse my hot-tub time with short, minute-long ice-cold showers in the morning.

The experience was, most of all, bracing. Also, an excuse to bellow like an ox. Honestly, it felt good, mostly, and the parts that were uncomfortable had me thinking about another Huberman point, which is that jumping into ice-cold water helps you be tougher. It really did help me stop flinching and feeling terror about it just to try it for a week. I would exit the shower feeling wide awake and enervated (and ready to jump back into the warm tub.) If it works for Action and Andrew, it works for me, too.

Non-sleep deep rest (NSDR) & yoga nidra

Yoga nidra is sometimes described as “yogic sleep” and involves reaching a point of consciousness between asleep and awake. Huberman’s lately been interested in a similar protocol he calls “non-sleep deep rest” (NSDR). Twenty to thirty minutes of NSDR every afternoon allows Huberman to “emerge feeling much more refreshed, with much more positivity.”

I followed Huberman’s ten-minute NSDR protocol video several afternoons. Though I don’t usually practice yoga or meditation, I found NSDR helpful, simple, calming, and even empowering. Long exhale breathing slowed my heart rate, and Huberman’s simple approach to controlling perception (closing my eyes, imagining looking down on myself from above, then shining a “flashlight” on different parts of my body to experience their sensations with full awareness) worked. I left feeling refreshed, wide awake, and ready to continue my day with curiosity.

Night

Most routines aim to provide structure to your day, but not dictate your life. Huberman’s is no different—even sunlight-obsessed, cold plunging, incredibly jacked neuroscientist winds down at the end of a long day. As you might expect, though, winding down for Huberman is a bit more nuanced than scrolling Twitter for an hour before calling it a day.

Huberman has often said the most important nootropic, stress reliever, immune booster, and emotional stabilizer is sleep. Huberman has struggled with his sleep quality in life, and uses a go-to sleep stack of magnesium threonate, l-theanine, apigenin, and inositol.

I am fortunate to sleep well without the help of sleep aids. But I did take note of Huberman’s other evening approaches: He dims the lights after 10 p.m. and reads every night.

This was, I found, a great way to drift off to sleep, focusing on the comfortable feeling of my tired body, my mind wandering to the massiveness of the universe, the incredible design of the human body, and all the cold-water-dips, relaxing meditations, and bright sunlight the next day would bring.

The Bottom Line

Huberman’s routine—particularly the addition of intermittent fasting, delayed caffeine, yoga nidra, cold baths, and bright sunshine—plugged in nicely to my life. Each element felt it added a focus to my own health, and after each I felt refreshed, relaxed, and ready to take on my day.