Turkey Bacon Is Healthier Than Bacon, But Is It Healthy?

- By Matthew Kadey, M.S., R.D.

- March 25, 2024

Few foods are as satisfying to the senses as bacon. That quintessential sizzle, smoky aroma, and umami goodness are almost irresistible. Unfortunately, pork bacon is high in saturated fat, sodium, and usually nitrates—which have been linked to cancer (1). For that reason, many people turn to healthier (or, at least, marketed as healthier) alternatives like turkey bacon. But is turkey bacon healthy?

What is Turkey Bacon?

Regular bacon comes from the belly, back, or sides of a pig, cut into slabs. Turkey bacon is pieces of meat from various parts of the bird, seasoned and formed into bacon-like strips. The result is a processed meat product that somewhat resembles regular pork bacon’s smoky, salty, meaty flavor—in a much less satisfying way. You can cook turkey bacon the same way as regular bacon: pan-fried, microwaved, or baked in the oven until golden and deliciously crispy.

Turkey Bacon vs. Regular Bacon Nutrition

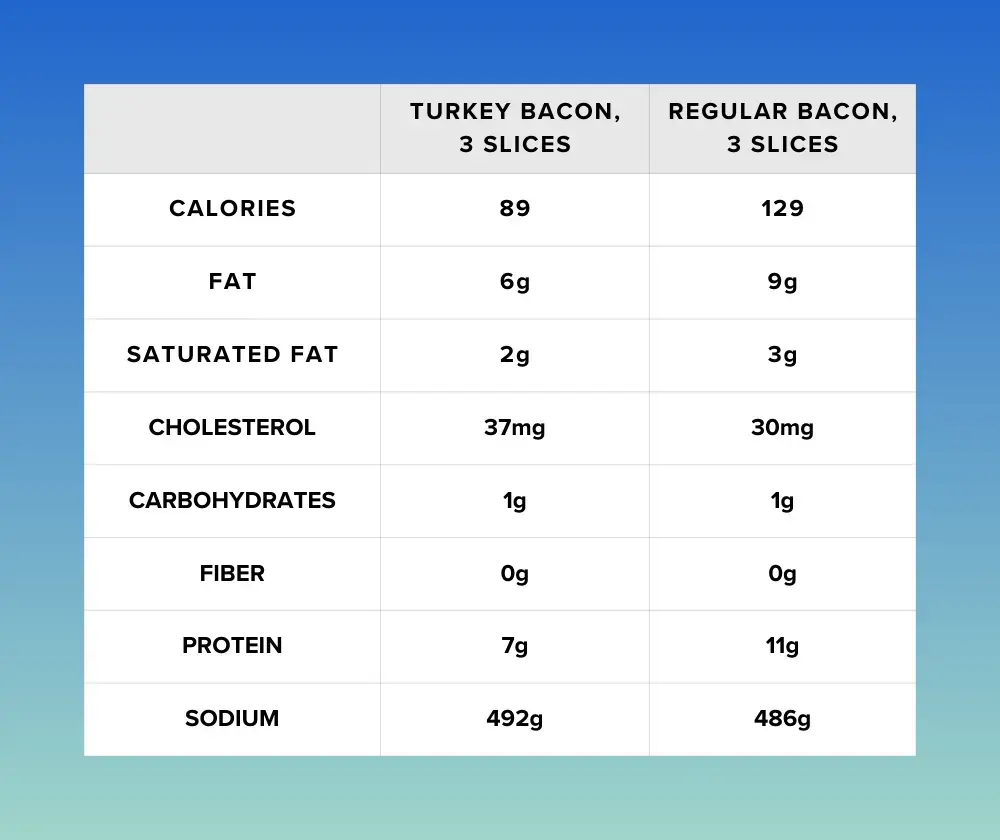

While turkey is a rich source of lean protein, once it’s processed into bacon form, it’s not as nutritionally superior to bacon as you might expect. Turkey bacon and regular bacon are pretty evenly matched, and in some areas—like protein—regular bacon has a slight advantage. It’s important to note, however, that the nutritional content of turkey bacon and regular bacon can vary based on brand. For example, one brand might have significantly more sodium than another, so check the labels.

Here’s how an average three slice serving of turkey bacon and regular bacon (prepared in the microwave) compare nutritionally, according to the USDA (2, 3):

Calories

Turkey bacon has about 30 percent fewer calories than regular bacon—a mere 40-calorie difference in a three-slice serving.

Saturated fat

Since white and dark turkey meat are typically used to make turkey bacon, the average saturated fat shakes out to less than a half-gram difference per slice (.67g per slice) compared to regular bacon (1g per slice).

The American Heart Association (AHA) suggests limiting saturated fat to no more than five to six percent of daily calories, since it can increase LDL cholesterol levels which has been linked to an elevated risk of heart disease and stroke (4). On a 2,000-calorie diet, that translates to 13 grams of saturated fat a day—which means you can still enjoy a couple slices of either type of bacon without maxing out on saturated fat for the day.

However, the AHA recommends limiting your intake of processed meats like bacon to a maximum of 100 grams per week (about 14g per day), so it’s best to avoid consuming this type of meat daily (5, 6).

Cholesterol

When eaten in appropriate amounts, both turkey bacon (37 mg per 3 slices) and bacon (30 mg per 3 slices) contain relatively low amounts of dietary cholesterol. For comparison, a large whole egg has 186 mg of cholesterol.

While cholesterol has gotten a bad rap in the past, current research generally does not support an association between dietary cholesterol and heart disease risk according to the AHA (7). However, the current USDA guidelines still suggest keeping dietary cholesterol consumption “as low as possible without compromising the nutritional adequacy of the diet.”

Some foods that include dietary cholesterol, like eggs, meat, and dairy products, can be an important source of protein, vitamins, and minerals for those consuming the typical American diet—which is why these foods remain part of the USDA’s “Healthy US-Style Dietary Pattern” (8).

Sodium

When it comes to sodium, turkey bacon (492 mg per 3 slices) and regular bacon (486 mg per 3 slices) have about the same amount. Neither is a low-sodium choice, considering the recommended daily maximum sodium intake is no more than 2,300 mg per day, and ideally no more than 1,500 mg per day (9). If you do eat either type of bacon, you’ll want to limit your intake and keep an eye on sodium in other areas of your diet to make sure you don’t go overboard.

Protein

Pork bacon has a clear advantage when it comes to protein (11g per 3 slices) with about 35 percent more protein per serving than turkey bacon (7g per 3 slices). For what it’s worth, for most adults, a meal should have at least 20 to 30 grams of protein—which means neither regular nor turkey bacon should be your only source of protein at a meal, especially if you’re trying to build muscle (10).

Vitamins and minerals

There are some subtle differences in vitamin and mineral content between turkey and regular bacon. For instance, pork bacon has higher levels of selenium and niacin, while turkey bacon comes out ahead for iron and vitamin B12—which play an essential role in energy production. But you shouldn’t eat the amounts of either type of bacon that would be necessary to meet your daily needs of these vitamins and minerals.

So, Is Turkey Bacon Healthy?

Unfortunately, no. There are several reasons why—like regular bacon—you shouldn’t make a habit of relying on turkey bacon for protein at breakfast:

It’s ultra-processed

Unlike a slice of oven-roasted turkey, turkey bacon is classified as ultra-processed—meaning it’s gone through a great deal of industrial processing (including the addition of additives) and no longer resembles its original form.

Many studies have found that regularly eating ultra-processed meats may increase your risk for poor health. A 2021 study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that consumption of processed meat may raise the risk of major heart disease and death (11). Evidence from other studies also suggest that eating processed meat, regardless of whether the meat is pork-based or turkey-based, is linked to an increased risk of health issues like type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and cancer (12).

It probably contains nitrates

Like regular bacon, most varieties of turkey bacon are preserved with nitrates or nitrites, which help reduce spoilage and enhance flavor, color, and texture. When heated, the nitrates or nitrites in turkey bacon can form nitrosamines—compounds that have been associated with health issues including an increased risk of certain cancers (13, 14). Because of this, the World Health Organization classifies processed meats like bacon (and turkey bacon) as a Group 1 carcinogen—the same designation as tobacco smoke (15).

Although “natural,” “uncured,” or “nitrate-free” bacon might seem like the obvious safer option, some natural ways of preserving meat, such as using celery salt or celery powder, still contain naturally occurring nitrates and the effects on the body remain unclear (16). In fact, some “nitrate-free” meats like bacon may contain more nitrates than conventionally cured options—meaning they may also carry a health risk (17).

Research suggests that consuming plenty of vitamin C and other antioxidants could help block some of the production of nitrosamines in the body—potentially offsetting some of the negative effects of eating processed meats (18). So, if you are going to eat turkey bacon (or regular bacon, for that matter), serve it with vitamin C-rich fruits or veggies like citrus fruits, strawberries, broccoli, and bell peppers.

It’s high in sodium

One slice of turkey bacon knocks out about seven percent of the 2,300 mg recommended daily maximum for sodium intake. Eat a few slices and the sodium racks up fast. A high-sodium diet can increase blood pressure and raise heart disease and stroke risk (9).

It’s often smoked

Yep, “smoked” turkey bacon tastes real good, and most options at the supermarket stamp it proudly on the label. Unfortunately, the smoking process produces certain compounds called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) which are believed to be carcinogenic (aka cancer-causing) when consumed in excess (20).

Cooking turkey bacon can be problematic

When meats are cooked over a blazing hot surface, like a frying pan, it can drive up the production of nasty compounds like PAHs—which have been linked to cancer (21). Roasting bacon at lower temperatures in the oven may be the best practice, since this method of meat and poultry preparation may produce fewer hazardous compounds (22).

It can be made with added sugar

Since turkey bacon contains less fat than pork bacon, manufacturers often add sugar to improve the taste and texture.

The added sugar in turkey bacon is relatively low—only a gram or two per serving. But since added sugars are often lurking in things like salad dressings, sauces, drinks, and many pre-prepared and packaged foods they can add up fast. To save a few grams, look for turkey bacon labeled “no sugar added.”

How to Choose Healthier Turkey Bacon

Not all turkey bacon is created equal. To choose the healthiest turkey bacon option available, read the ingredient list and nutrition facts label.

Check the nutrition facts

Pay special attention to these numbers on the Nutrition Facts panel. When you’re selecting a product, it’s particularly important to look for options with lower amounts of saturated fat and sodium.

It’s also important to consider the number of pieces in a serving size listed on the Nutrition Facts label versus how many you might consume, as most people will consume more than one slice of bacon.

Check the ingredients

All turkey bacon is processed, but some ingredient lists read much more like a chemistry quiz than others. Usually, when it comes to ingredients, less is more.

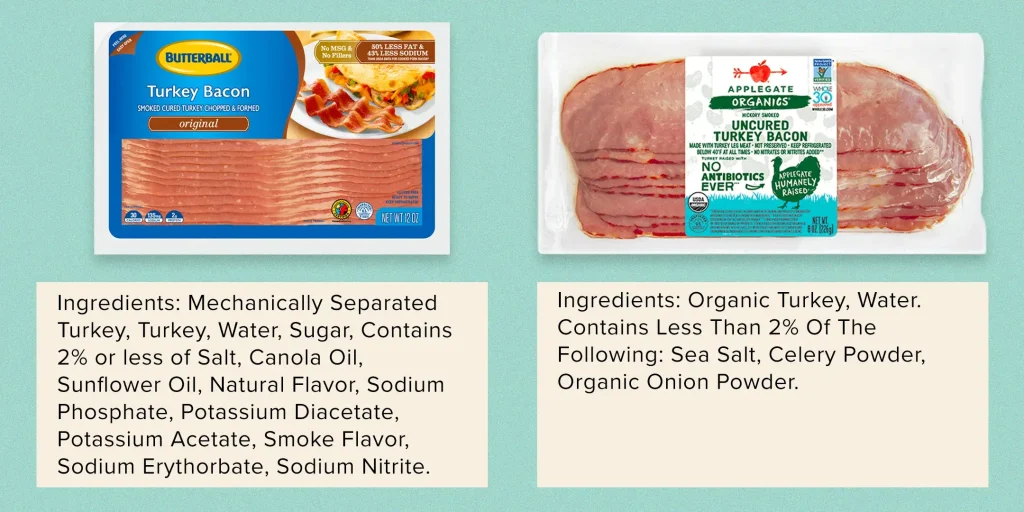

Take the ingredients list for these two popular brands, for example:

Between the two, Applegate Organic Turkey is the obvious choice. The Butterball Turkey Bacon not only contains added sugar, seed oils, and nitrites; but, it’s clear the meat is more processed by the indication of “Mechanically Separated Turkey,” and a string of questionable preservatives in the ingredients list.

The Bottom Line

Turkey bacon isn’t healthy. While it has less calories and saturated fat than regular bacon, turkey bacon is still ultra-processed, high in sodium, and often contains cancer-causing compounds like nitrates and PAHs. That said, it’s important to keep the dangers of turkey bacon in context. The risk is magnified for people who eat processed meats every day compared to eating the occasional breakfast bacon as part of a diet that is otherwise rich in nutritious whole foods. To keep health in check, treat turkey bacon like regular bacon—keep the serving size to 2 or 3 slices, and don’t make it an everyday habit.

References

1. Karwowska, M. et al. (2020). Nitrates/Nitrites in Food—Risk for Nitrosative Stress and Benefits.

2. USDA (2018). Bacon, Turkey, Microwaved.

3. USDA (2018). Pork, Cured, Bacon, Cooked, Microwaved.

4. American Heart Association (2021). Saturated Fat.

5. American Heart Association (2023). Here’s the Latest on Dietary Cholesterol and How It Fits in With a Healthy Diet.

6. Schoenfeld, B. et al. (2018). How Much Protein Can the Body Use in a Single Meal for Muscle-Building? Implications for Daily Protein Distribution.

7. Iqbal, R. et al. (2021). Associations of Unprocessed and Processed Meat Intake with Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease in 21 Countries [Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Study]: A Prospective Cohort Study.

8. Quian, F. et al. (2020). Red and Processed Meats and Health Risks: How Strong Is the Evidence?

9. Li, L. et al. (2012). Influence of Various Cooking Methods on the Concentrations of Volatile N-Nitrosamines and Biogenic Amines in Dry-Cured Sausages.

10. Stuff, J. et al. (2009). Construction of an N-Nitroso Database for Assessing Dietary Intake.

11. Chazelas, E. et al. (2022). Nitrites and Nitrates From Food Additives and Natural Sources and Cancer Risk: Results from the NutriNet-Sante Cohort.

12. World Health Organization (2015). Cancer: Carcinogenicity of the Consumption of Red Meat and Processed Meat.

13. Jen, S. et al. (2018). Natural Curing Agents as Nitrite Alternatives and Their Effects on the Physicochemical, Microbiological Properties and Sensory Evaluation of Sausages During Storage.

14. Pennisi, L. et al. (2020). Effects of Vegetable Powders as Nitrite Alternative in Italian Dry Fermented Sausage.

15. Sebranek, J. et al. (2007). Cured Meat Products Without Direct Addition of Nitrate or Nitrite: What Are the Issues?

16. Tannenbaum, S. et al. (1989). Preventative Action of Vitamin C on Nitrosamine Formation.

17. Mirvish, S. et al. (2008). Effect of Feeding Nitrite, Ascorbate, Hemin, and Omeprazole on Excretion of Fecal Total Apparent N-Nitroso Compounds in Mice.

18. American Heart Association (2023). Shaking the Salt Habit to Lower High Blood Pressure.

19. Afe, O. et al. (2021). Chemical Hazards in Smoked Meat and Fish.

20. International Agency for Research on Cancer (2015). Q&A on the Carcinogenicity of the Consumption of Red Meat and Processed Meat.

21. Pensabene, J. et al. (1974). Effect of Frying and Other Cooking Conditions on Nitrosopyrrolidine Formation in Bacon.